Political amnesia on Venezuela

Re-writing the Bolivarian revolution

The following passage is from an article I wrote for the Independent back in 2012.

According to the International Trade Union Confederation’s 2012 annual survey, “anti-union discrimination, violations of collective bargaining rights and the non-respect of collective agreements were frequent and persistent in both the public and private sector”.

After leading a 15-day strike at the state iron mining company in 2009, [one trade unionist] was jailed for seven years for “crimes” that included unlawful assembly, incitement, and violating the government security zone. According to The Human Rights Foundation…his imprisonment had more to do with the fact that he took workers out on strike than with any of the trumped up official charges.

The country in question was Venezuela, where Hugo Chávez had recently won a presidential election. Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution was a great cause célèbre on the left. I remember attending meetings in London as a student activist and seeing members of Socialist Action (a tiny Trotskyist sect linked to then mayor of London Ken Livingstone) wearing tracksuits bearing the yellow, red and blue of the Venezuelan flag. As the Coalition government was implementing austerity in Britain, Venezuela was supposed to demonstrate that ‘another world’ was possible.

There are plenty of things I got wrong during the past 15 years. I didn’t think Britain would vote to leave the European Union in 2016 nor that Russia would invade Ukraine in 2022. But for the most part I was right about Venezuela. The abuses I have mentioned above were not excused as part of a ‘dialectic of history’ as the punishment camps in the Soviet Union had been; on the left they were simply ignored - and anybody who mentioned their existence was ostracised in bien pensant circles.

That notwithstanding, it was obvious to anyone with even a passing knowledge of Latin American politics that Hugo Chávez - and later his successor Nicolás Maduro - had more in common with Fidel Castro than with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

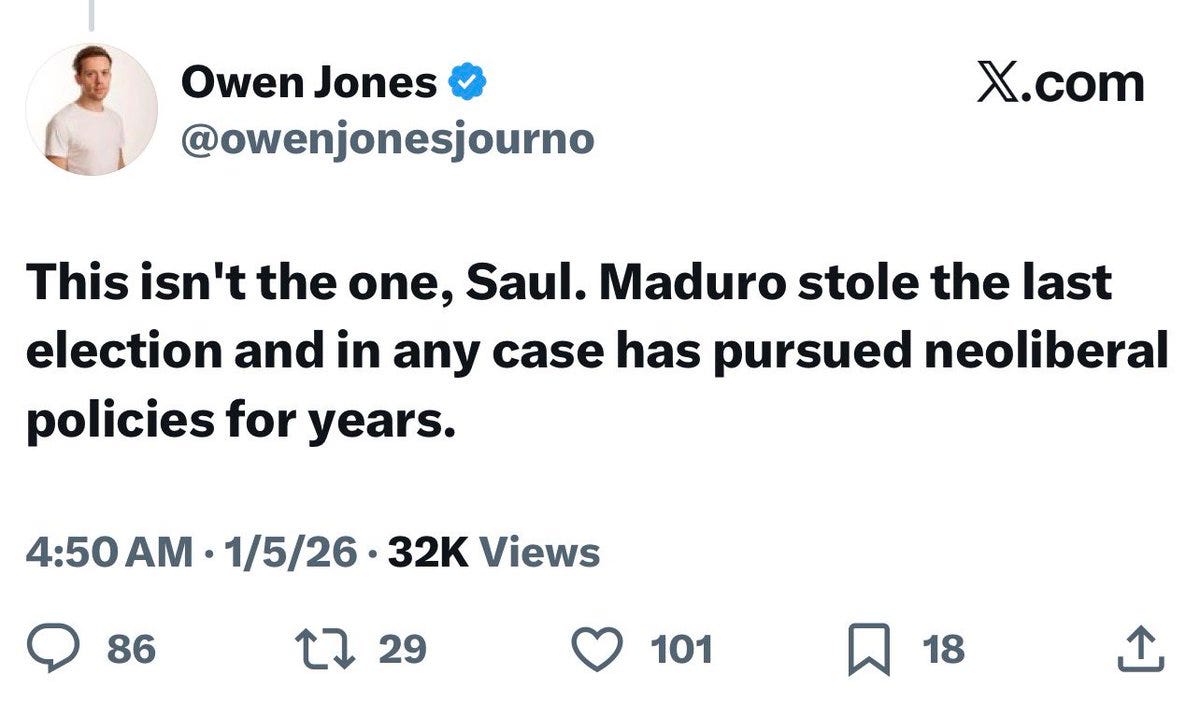

Not that this prevented the then Independent columnist Owen Jones from describing Chávez as someone who led a “progressive, populist government that says no to neo-liberalism”. Jones even went on a pilgrimage to Venezuela during this period to act as an ‘election monitor’. When he returned he informed readers that Venezuela was “an inspiration to the world, it really does show that there is an alternative”.

Two years later, when students in Venezuela were demonstrating against Maduro, Jones penned another column for the same newspaper claiming that the post-Chávez government was being unfairly maligned. Though prepared to concede that Venezuela was not ‘some sort of paradise’, he nevertheless proceeded to paint those protesting against the government as dupes of the CIA who were agitating for a ‘Pinochet-style coup’. Indeed, once the throat clearing was out the way it was more or less business as usual.

As for the government’s much-maligned democratic credentials, when Chávez was elected in 1998, he received 3.7 million votes against the opposition’s 2.6 million. In 2013, his successor Nicolás Maduro received 7.6 million votes, against the opposition’s 7.4 million.

Democracy is as much about what happens between elections as what occurs on the day of the vote; you don’t need to be shoved into a voting booth at gunpoint to live under a tyranny. Hungary is a similar example closer to home, the main difference being that it is conservatives rather than socialists who are prepared to tell lies about the country.

Or when things get too bad simply never mention the subject again. Jones was hardly alone in this: in the mid-to late 2010s it became deeply unfashionable in left-wing circles to talk about the so-called Bolivarian revolution, which was treated as an embarrassment best forgotten. The country, and the people who lived there, might as well have ceased to exist. When inflation reached the hundreds of thousands of per cent, when journalists were imprisoned, when Maduro rigged the National Assembly so only his supporters could win, when armed militias (the colectivos) rampaged through the country murdering and disappearing people with impunity - all that could be heard was the sound of crickets.

Now that the United States is involved, many of the same people have reemerged from their self-imposed voeux de silence, only to claim a monopoly of insight into the region. Having condemned Trump’s abduction of Maduro, Jones has been forced to account for the fact that the deposed Venezuelan dictator was ‘not a good guy’, as BBC journalists like to say. But he wasn’t one of us either.

There are times when one can witness history being re-written in real time. Faith consists in believing what reason will not believe, as Voltaire put it.

Obliged to acknowledge the existence of Venezuela again, left-wing intellectuals have reached for the familiar backstop of a ‘revolution betrayed’, either by Stalinist purges or Thermidorian reaction. Maduro is a tyrant and a crook but he wasn’t a true socialist. Thus Chávez and Maduro’s irresponsible European and North American admirers get off scot-free. The highest priority is once again to ‘save’ socialism from its actually existing practice.

The individuals involved may wish to preserve their reputations but I suspect such historical revisionism does more damage in the long run. Why do so many revolutions end in squalor, corruption and brutality? Did Venezuela’s oil industry collapse because it was too neoliberal, or because political loyalty replaced technical expertise as a precondition for employment? Is a cult of personality such as that which surrounded both Venezuelan leaders inevitable when advancement in any field is contingent on being a ‘yes’ man? Does it help or hinder the left if all inconvenient facts are stashed away in a drawer marked ‘forgetting'?

For Venezuelans themselves these things really did demonstrate that another world was possible, in many cases one of hunger, grief, fear and uncertainty. I suspect some of them were disappointed to find that their erstwhile comrades had moved on to pastures new.

Left-wing commentators are fond of throwing around a quote by Antonio Gramsci about the old dying and the new struggling to be born. But socialists would do well to consider how this might be applicable to their own project. If socialism and social democracy are in the doldrums, it is partly because genuine historical accounting has rarely taken place. Instead we hear over and over how the city on the hill was thwarted by the machinations of the United States. Perhaps so, but it never tells the full story.

In practice, anybody who attempts to grapple with the downsides of state socialism (and whether or not some flaws may be inherent) is treated with suspicion on the basis that there should be no enemies on the left. And yet ordinary people - who aren’t animated by the same faith as the likes of Jones et al - can hardly fail to notice these outbreaks of epistemological double vision.

What does any of this matter when Trump and Putin are carving up the world? Probably not much. But as a socialist I happen to think the health of the left is quite important. Internationalism should also mean something beyond a mouthful of empty slogans.

Alternatively, you might consider buying my book.

I think the reasons that "socialism and social democracy are in the doldrums" are different. Social Democratic parties have continued to follow flawed, and frankly reactionary, Third-Way Neoliberalism; Meanwhile many Socialist parties both advocated for an outdated & overly-centralized economic system (i.e., insisting on Marxist economics instead of Mutualism) while defending authoritarian countries that had beef (justified or not) with the USA and/or UK.

We need something that recognizes private property as a negative right while also preventing the centralized ownership of said private property (i.e., anti-trust laws and Land Value Tax). It must also redistribute excess money to uplift the less fortunate, and as previously mentioned, prevent the centralization of private property in the hands of a few. Last but not least, the right to join a union as declared by the National Labor Relations Act (1935) signed into law by FDR.